wcaleb Archive - index - about

Josephine Nicholls Pugh Civil War Account

An account of Civil War events in Assumption Parish, LA, during 1862, focusing on how Union occupation disrupted slavery and plantation operations in the area.

Josephine Nicholls Pugh

Records of Southern Plantations from Emancipation to the Great Migration, Series B, Part 3, Reel 7, Frames 487-498

Image scanned from 35mm microfilm published by UPA. Published here by W. Caleb McDaniel.

ca. 1865

This item is published solely for personal research and nonprofit educational use under the terms of fair use. No copyright in the item is asserted or implied by its publication here.

Text

CFCF8F82-3E00-4779-AA6B-FABFC6CBCD19

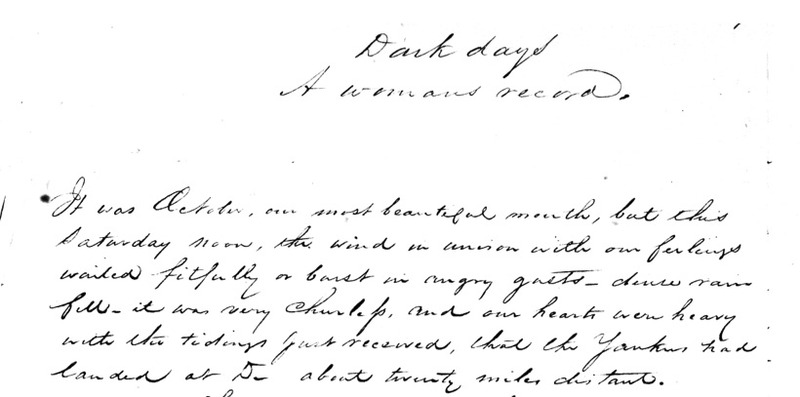

Dark days

A womans record.

It was October, our most beautiful month, but this Saturday noon, the wind in union with our feelings wailed fitfully or burst in angry gusts, dense rain fell. It was very [illegible], and our hearts were heavy with the tidings just received, that the Yankees had landed at D___ about twenty miles distant.

This army would soon be upon us, and war, with all its attendant horrors. Heretofore we had suffered privation and discomfort, but had easily reconciled ourselves to them, having in the beginning of the terrible struggle determined that all superfluities should be dispensed with to aid our country’s need. Alas! not called on our foes gathered the surplus.

Toward night The wind increased in violence, blowing shifting to

the Nor. West towards night, which was a sleepless night to most of

us. We knew not, what the morrow would bring forth. Our small, poorly

clad & worse armed force, almost destitute of ammunition, could scarcely

contend with Gen. Weitzel’s thoroughly equipped troops, composed of a

well disciplined infantry and cavalry mounted on horses, but lately the

pride of Southern stables. Coming thus with the pride and circumstance

of war, they were well calculated to inspire awe, and terror, in the

inhabitants, but I think indignation was the predominant feeling, with a

sense of depression at the helpless condition in which they were placed.

There was great confusion on Sunday, hurrying to and fro. Our men fell

back. Poor fellows they were ill fitted to [illegible word crossed

out] resist that dazzling array. even the Their officers even were

coarsely dressed and showed no uniformity of attire.

On the black race, show and glitter exercise the strongest influence. No

wonder then, that drawing outward comparison, they yielded religious

belief to Yankee supremacy. They saw their masters leaving their

homes—they knew not with what prospect of return. Their faith could not

stand the test, and numbers flocked to the Yankee Standard, forming a

motley, grotesque, and increasing army multitude.

Many of our planters, in anticipation of such an invasion had left with their negroes for Texas. After reflection we had decided to remain, knowing the aversion of the negro to breaking up and moving to a new country, thinking too that their demoralization would be less complete at home.

Most of ours were inherited. We hoped at least a majority would

remain continue with us. If there was confusion and hurrying

without, there was none the less within. Many planters were at the last

moment collecting all their household goods, hastened to escape with

their families. And there were sad, brief partings. We wives insisted

that our husbands should leave us. Why remain to fall into the merciless

hands of Butler? to be hurried we knew not whither, nor to what fate.

Rumor heralded the arrest and imprisonment of prominent men in N.

Orleans. Ours might still escape, or conceal themselves for a time until

the enemy’s policy could be known.

We were not afraid to stay behind, and so it was our large household for the first time in a season of affliction was bereft of its proper head. His stay could only have added to our distress, and so he parted from us that Sunday afternoon, while the army lay encamped a few miles off. Thus the responsibility rested solely with me, for within a few hours, the overseer becoming alarmed, also left. Of this I was immediately informed by our confidential man who came to receive instructions. He had ever been implicitly confided in, but was somewhat timid; however, I thought in his character of preacher he would exercise a good influence over his people. I instructed him to keep them together, if possible, and call them to their usual avocations in the morning. He came at daylight to inform me that some of the young men had left during the night, and he feared others would follow. But a large number were still working under the driver’s direction, one of their own color who was popular among them.

At breakfast on Monday our dining room servant, a young man whose

ancestors had been in the family for generations, told me the army was

approaching and a squad in advance had shot down and killed one of our

neighbors, a young man who had been discharged from the army on

account of ill health from the so called Confederate army. He was on

horseback having sent his wife and child on to a neighbor’s house,

hoping still intending to make his way out of the country. Before he

was aware, he was surrounded by soldiers and summoned to surrender.

Wheeling suddenly, he plunged his [illegible] into his horse and

dashed off. A dozen rifles were discharged, raising himself from his

saddle he fired among them and fell dead. His horse was captured and

mounted by one of the troopers, who with others rode into the next yard,

where on the gallery stood the wife awaiting her husband. She recognized

at a glance the noble animal—seeing this the soldier said, “If you wish

to bury the man, who rode this horse, his dead body lies in the road, a

short distance back.”

On came that martial host, proud and powerful, but I looked not

[illegible word crossed out] on their ranks, glittering in the

sunshine, when all was so dark to us. In sorrowful indignation, drawing

my little ones around me, I sat in the library awaiting their approach.

I might close doors and windows, shut them out from sight, but there was

no closing the ear to the great tumult, that Babel of voices, that tramp

of a thronging multitude.

Armed men were every where, surrounding the house, demolishing fences,

trampling the flower beds, in to the negro quarters, to the stables, to

the fowl yard, kitchen, but as yet they had not invaded the house. I

prayed fervently they might not. Should they attempt this, I would

invoke the protection from their officers, which I could not bear to

do in presence of my boy, a stripling of fourteen. He stood by me with

swelling heart, flashing eyes and wrath only subdued from rash

demonstrations by his love for me.

I am was ignorant of the insignia of rank, but an officer soon

entered the room. Some one said he was a Major. I am glad he was not an

American. Coming towards me without salutation he said “I want some

coffee, get some for me at once.” “I have none sir.” He retorted with

“that’s a lie” and walked out.

I could sit still no longer, but went to the kitchen, where sat old

Hetty looking angrily at the soldiers who filled it. Calling her to me,

I was about giving some directions, when I saw a soldier and a youth

riding towards the stable. In the impulse of the moment I called to them

“Gentlemen, if you are gentlemen” (the man turned slightly on his

saddled and looked at me) “is it customary for Union soldiers to pay no

regard to ownership.” "There is no ownership here Madam, this place is

confiscated." "That is yet to be seen decided, Sir." “Might makes

right,” he answered, “and I shall help myself from your stables.” “I

have no power to resist.” Something more I may have added. I do not

remember, however the boy’s ire was excited: and he pointed his

cocked revolver at me. Albert, my servant, previously [illegible]

in some alarm, putting his hand on my shoulder said “Come away,

mistress, these men will hurt, or insult you.” A messenger now came and

informed me that an officer desired to speak to me.

Time will not soon erase [illegible words crossed out] that interview.

The weather was cold, but I did not feel it. I stood in the Gallery

surrounded by ladies and children, (for our family had been increased by

refugees) a legion of frightened servants, curious and eager to hear all

that passed pressed around. Several officers advanced one addressed

me. “Is Col ___ at home” said one, giving me a military salute. “No

sir.” “I knew it before asking.” “Then, sir, the question was

unnecessary.” With a swap of his arm, he now and in a loud tone, he

informed me that he was the Provost Marshall of the whole Brigade. I

bowed. Turning he pointed to two darkies. "Madam, these men were

arrested while stealing your chickens poultry. I have given you

protection." At this I felt the dilation of my throughout, the chord

like swelling of its veins. Drawing myself up, I replied “I thank you

sir if you have afforded it, saving a few chickens is a poor protection,

when all the valuables belonging to the plantation have been taken. Your

soldiers have seized the mules, wagons and every horse; sir, even my

little boy’s pony with his fancy saddle is being ridden off,” pointing

as I spoke to the youth who had stolen them, “and there goes another

with my daughters side saddle.” He responded with indignation, “Madam,

this is the first place, where any complaint has been made of the Union

soldiers.” "Others may have suffered less or feared to speak. These

ladies have seen several of our male men negroes knocked down, and

pistols applied to their heads to force them off. Your soldiers have

placed knapsacks on their shoulders. They had no option but to march.

Sir, I wish none to remain who desire to go, but there are many who will

not do it voluntarily. Do not permit force to be used against those,

born and (reared with us I should have said, but inadvertently used the

word) educated."

“Educated Madam?” he said with a sneer. “You hesitate at the word.” “Fully as well,” I unwisely responded, “in morality and principle as your men who are perambulating every where, stealing all they can lay hands on. When my husband left us, he thought there were gentlemen in the Union Army who would protect ladies from insult.” “Do you mean to insinuate that there are no gentlemen in the Union Army?”

“I’m not so unjust sir, there are gentlemen in your army, as there are

some who are not so in ours.” Advancing still hearer and speaking in

an with excitement he said, “Madam, your son alone protects you.” “Sir

I do not claim the prerogative,” and casting off the shawl thrown around

me by some friendly hand, I looked at him with unflinching eyes. It

might have been wiser to have spoken differently but it was not in me,

surrounded by that reckless soldiery, thus violating the sanctity of my

home.

The Dutch Major now approached and supposing that I was asking for protection said “This lady claims protection does she? Yet when I asked for coffee, she refused saying she had none, where she had it.”

“Sir I only ask protection for my household against insult, and Sir, (turning to the Provost) language such as this, is considered as an insult by a Southern woman.”

Let me pause to do Justice, several of the officers felt for me, and

seemed somewhat ashamed of their Provost. The speakers. One now

spoke and said, "Such language is insulting. If Mrs ____ said she

had no coffee, she had it not you should have believed her." “I have

it Sir but not for him, an invalid my husband procured some for me, with

difficulty and at great expense. No Southern man would touch it, but if

you gentlemen desire to it, order one of my servants to prepare it for

you.” The officer answered deprecatingly, and said “we do not wish it.”

And turning their horses heads they galloped off. The army took eighteen

mules, the wagons, harness, horses and saddles and all the negro men,

they could lay hands on.

[Final paragraph crossed out.]

Manuscript, 8 pp.